On Misaligned Incentives in HealthTech

The Value Transfer Levy and the counter-intuitive economic climate for innovative tools in public hospitals

The first question emerging healthtech entrepreneurs should ask themselves is "Who will get the most value from my product?". The second question they should ask themselves is "Who is going to pay me for my product?". If the answers are not the same, you've got a problem.

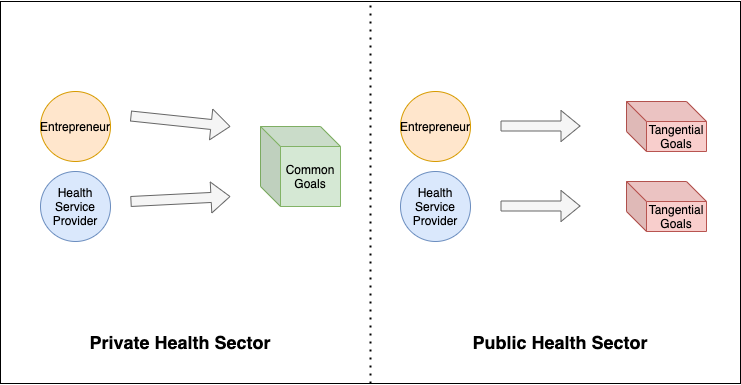

Within publicly funded health services, it's harder than you might think to arrange incentives in such a way where all parties to a technology project have the same agenda. Let me explain.

In January, I left full-time medicine to pursue a career on the boundary between clinical medicine and health technology.

In the 4 months or so since I made that career move, I've built and deployed 3 software tools of various sizes. It's early days, but I'm yet to find a way I can deploy these tools in a way where I can capture some of the value that I've created.

Simply put:

It's not easy to deploy tools into public hospitals and get paid for it.

Earlier this year, I launched Rapid Access to Forms (Rapid AF), a mobile app that turns any hospital fax machine into a distribution centre for paper forms. This makes finding any of the 5000 paper forms at paper-based hospitals far more time efficient.

If we ask ourselves question 1 from above, we quickly realise that it's the junior doctors, nurses and ward staff who typically get the most value from Rapid AF. It might save them on the order of 10-15 minutes each day looking for these forms.

However, if we ask ourselves question 2, "Who is going to pay me for my product?", it's apparent that it wouldn't make sense to ask employees within a hospital pay for a tool that makes working there easier. It has to be the institution, given that it's a workplace process.

Here we encounter a problem.

When you ask for money in exchange for a product, the easiest way to justify your asking price is to point at a Painful Problem that your customer is experiencing and say "For n dollars I can make that 2n sized problem go away".

When your payers are not your users though, playing on that Painful Problem becomes substantially more difficult. And the further your payers are away from your users operationally, the more difficult this becomes.

Painful Problem is much less painful and is much easier to ignore if it's not affecting you directly. This is human nature.

Within large enterprises like hospitals, payers are often so operationally distant from doctors, wards and nurses that most hospital clinical staff can't even tell you the names of the people making financial decisions for that area. As a result, there's typically little to no communication pathways between the two.

This leaves a large burden on the innovator to provide quantitative metrics to justify their project. This would not be unreasonable if there were widely available performance metrics to benchmark your tools against. However there typically aren't. So for tools that don't directly impact things like length of stay, number of procedures performed, number of clinic appointments and so forth, building the infrastructure to justify a business case is often far more difficult than building the innovative solution itself!

This means that there are entire cohorts of small and medium-scale workflow problems in our hospitals that might never be solved because the burden of proving the size of the problem is many times bigger than the problem itself.

(For a real world approach to this problem, check out Robert Buehrig and his tool suite at Cogniom).

The Value Transfer Levy

Now, I don't mean to paint administrators and payers within hospitals in a negative light. They're an important part of the team in that they ensure the financial sustainability of our health services by hitting government KPIs and bending over backwards to meet at times impossible budgetary constraints.

And they do typically understand and empathise with the plight of their staff elsewhere within their organisation. Although, in a phenomenon I'm dubbing the Value Transfer Levy, they might give you recognition for one tenth of the value you provide to other people within their institution. There seems to be a natural tendency to value problems in our own domain far greater than those outside it, even for the most well-intentioned people.

This is evident in mankind's response to climate change, racism, refugee rights and so on.

The Value Transfer Levy occurs when a user of a product is not the one paying for it, and the payer for that product only recognises a proportion of the value the user receives.

To be clear, I don't want people to view this post as a complaint about why my products are yet to seek widespread adoption yet. Rapid AF has lots of problems, and by most metrics is objectively a bad product.

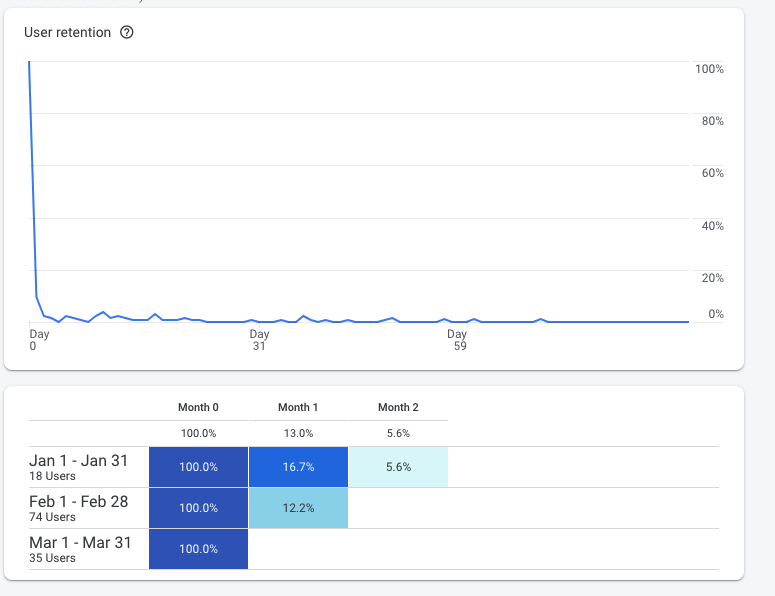

If we look closely at Rapid AF's user retention curve, we can see it has an abysmal 5.6% 2 month retention rate:

Objectively, users who use the app don't come back very often. This is a red flag. There are multiple reasons for this, and it may be the subject of a future blog post.

Gustaf Alstromer (@gustaf), former early growth marketing employee at AirBnb defines user retention as the single most important metric to determine a product's success. (Far more important than static metrics like total user signups, downloads, and views). Specifically, "do users come back in the future and receive repeated ongoing value?".

So clearly the Value Transfer Levy isn't the reason Rapid AF hasn't gone global. But there are many other instances where misaligned incentives can harm innovation in public hospitals.

Quirks of Hospital Funding Models

If I told you that I could hypothetically build a tool that would let a hospital do double the number of knee replacement operations they currently do, you might assume that would be a slam dunk value proposition, no?

Perhaps in the private sector it would. But in the public sector, depending on the applicable funding model, unit economics begin to break.

Hospital funding is a complex topic that I won't begin to pretend to understand fully, but what I can say is that the Australian Government does not write a blank cheque for hospitals to fill up with costs of their own choosing.

They set targets and limits for different types of service provision, and will only pay for growth in those costs at a rate of around 6.5% per annum. So for a public hospital that doubles the number of knee replacements they can do overnight, they'd actually end up getting paid far less per operation than beforehand.

So as a result, public hospitals don't want tools that can help them double their knee replacement count from 100 per month to 200 per month. If anything, they want analytics tools that can help do exactly 100 operations, and not a single one more, because that's the point on the curve where they receive the highest revenue per operation.

This creates a counter-intuitive economic climate for innovative tools that facilitate more output. The incentives are not always clearly aligned.

This is why I'm now advising that emerging healthtech entrepreneurs think very early about their business model. We can't afford to think like Silicon Valley-at-large and say "I'll build a big user base and the revenue will follow", because those assumptions break down rapidly in the public sector.

Most innovators are probably better off targeting the private sector where more operations directly results in higher earnings. This is of course a real shame for entrepreneurs who want their innovations to benefit the lives of society's most marginalised.

And while there are solutions to each of the above problems individually, given how difficult business is already, why would you try to solve these problems? Why wouldn't you just build your business in a way where the incentives are aligned from day one?

All of this turns entrepreneurs away from the public hospital sector, and stagnates progress.

With all of that said, I'm taking a break from building tools to sell to hospitals directly, and am now instead working on Olog, a free shift tracker and overtime log designed to help doctors in hospitals maximise their overtime entitlements.

Because at least this way, the project incentives will be aligned.